When the Numbers Start Screaming

Student unions are supposed to be uncomplicated in principle. Students pay fees. Those fees fund services, events, advocacy, and the infrastructure that makes campus life livable. When something goes wrong, explanations follow. But explanations are always secondary. The numbers come first.

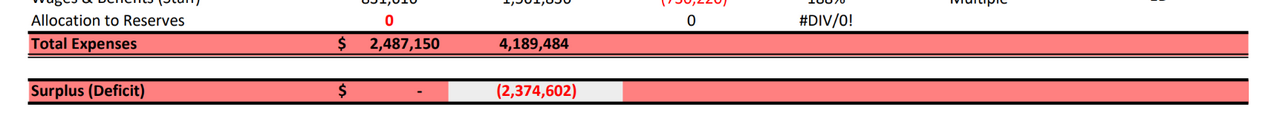

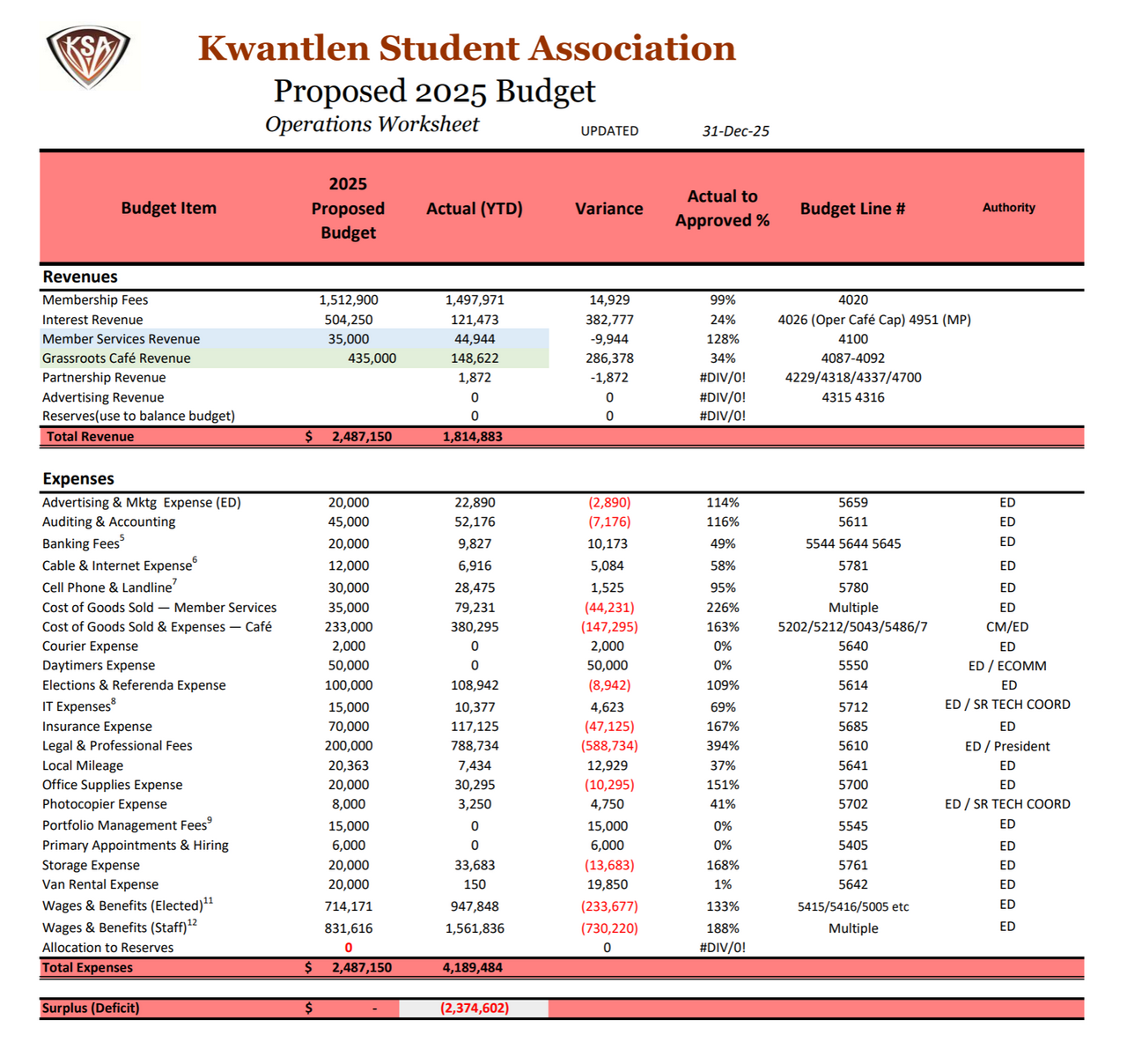

The Kwantlen Student Association’s 2025 financials tell a story that is just too difficult to soften. The association’s core operations ran a deficit of more than $2 million. Not because students stopped paying fees. Membership revenue largely came in as expected. The problem was spending.

Image: The 2025 December budget released by the Kwantlen Student Association, under the oversight of 2025 VP Finance and Operations Manmeet Kaur.

Legal and professional fees were budgeted at roughly $200,000. Actual spending approached $800,000 — nearly four times what had been approved. Lawyers are sometimes necessary. Contracts require review, disputes require counsel, risk must be managed. But when legal fees rival the cost of entire student programs, they cease to look incidental. They begin to look structural.

A budget cannot explain why legal costs exploded. It simply records that they did. But a reasonable interpretation follows:

Strategic decisions appear to have been increasingly outsourced to counsel rather than resolved transparently within elected governance.

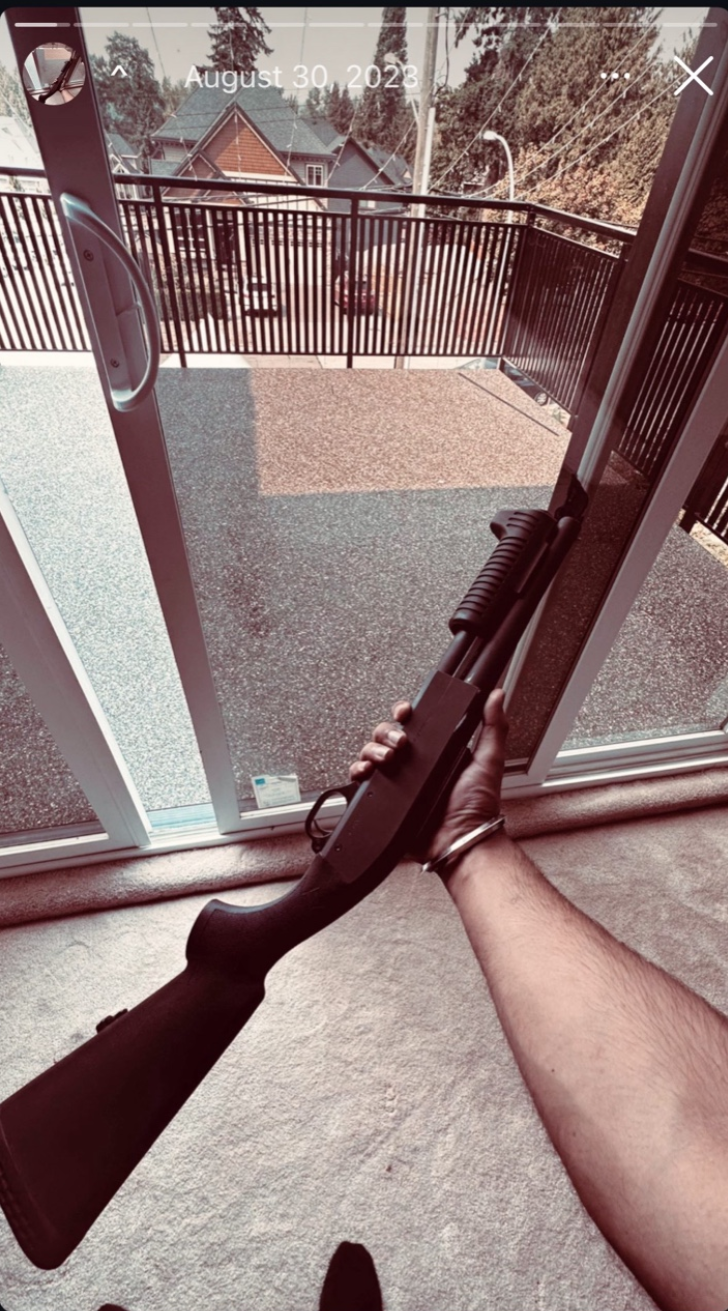

This is what happens when an Executive Director who was not properly vetted and allegedly was deemed to have overexaggerated their experience is hired to lead. In 2023, resigned counsel David Borins of Borins & Company allegedly informed then KSA president Abdullah Randhawa that hiring his friend was problematic:

Abdullah [Randhawa],

There is nothing in your email below that changes the view expressed in my letter of December 6, 2023. You had previously advised me in September 2023, both in discussions directly with you and when we spoke to Chris Girodat together on a Teams meeting on September 14, 2023, that Timothii Ragavan is a friend of yours. You admitted that your conduct in attempting to influence Mr. Girodat, and others, to see Mr. Ragavan be hired as ED, was inappropriate. You claimed that you had misunderstood your obligations based on your inexperience, but that if given another chance, you would allow Mr. Girodat to carry out his obligations without interference.

It is the same this time around, you are still in a conflict of interest as you actively participated in Mr. Ragavan being selected as the new ED. Moreover, you assured me when we spoke on Teams on Monday December 4, 2023 that the ED hiring committee was only considering candidates that Chris Girodat had short-listed. As you are aware, Mr. Ragavan was not short-listed. In fact, he was rejected as an ED candidate by Mr. Girodat for lacking experience and because Mr. Girodat felt that Mr. Ragavan had exaggerated his experience on his resume by claiming to have held Executive Director positions in the past when he clearly had not. Yet, on a suspiciously short timeline, all while entirely excluding Mr. Girodat and any external advisers from assisting with the process, you went ahead and oversaw Mr. Ragavan being hired as ED. Mr. Gregory, as a non-voting member of the Committee was also excluded.

All of that said, I would very much like to see the KSA properly governed. I have a deep knowledge of the KSA and I believe I can assist with that stated goal. So, if you want to discuss the conditions under which I would consider being retained once again by the KSA, I would only do so if you agree that KPU administration is part of that discussion. This is because, in the current environment of the KSA (i.e. – no experienced or objective KSA management), my view is that to ensure the proper governance of the KSA, the University's assistance and oversight at this point in time is essential. If this is acceptable to you, (i.e. – that KPU be involved in a discussion regarding the possibly of KSA retaining Borins & Company once again as legal counsel), please advise by return email and a discussion can be commenced.

In closing, I want to be clear, Borins & Company is currently not serving as legal counsel to the KSA and we are not in this email, or otherwise, providing any legal assistance or advice to the KSA.

Regards,

David Borins

Student money, in that case, is no longer primarily funding services. It is funding risk containment.

Compensation tells a similar story. Wages and benefits for elected officials reached nearly $950,000, well above projections. Staff wages climbed to approximately $1.56 million — dramatically exceeding budget. Compensation is not inherently suspect. Organizations require people. But when payroll expansion coincides with large operational deficits, scrutiny becomes unavoidable and mandatory. Students are entitled to ask whether staffing levels and compensation structures are aligned with actual service delivery.

What exactly was the return on investment (ROI) of such ballooning expenses? Did students actually gain anything meaningful or was it spent on the enrichment of only management, the board, and executives?

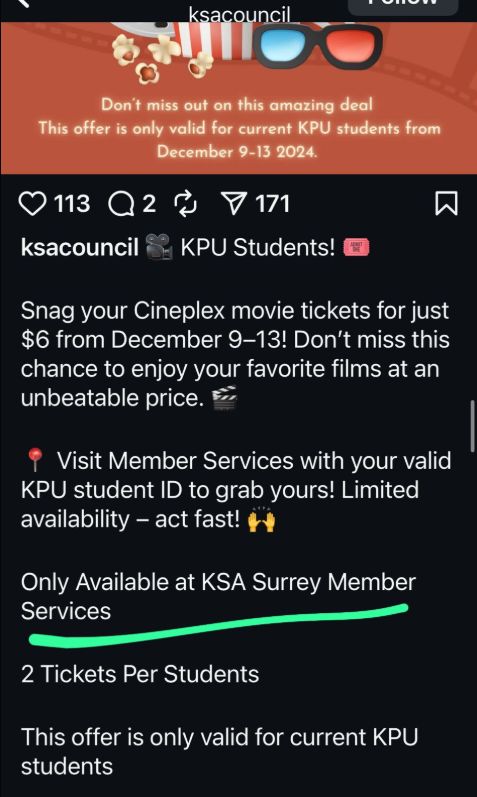

Meanwhile, parts of the service side appear comparatively restrained. Several student-facing budgets were underspent or barely executed at all. That contrast is striking. The association did not collapse under the weight of excessive bursaries or runaway mental-health programming. It collapsed while administration expanded.

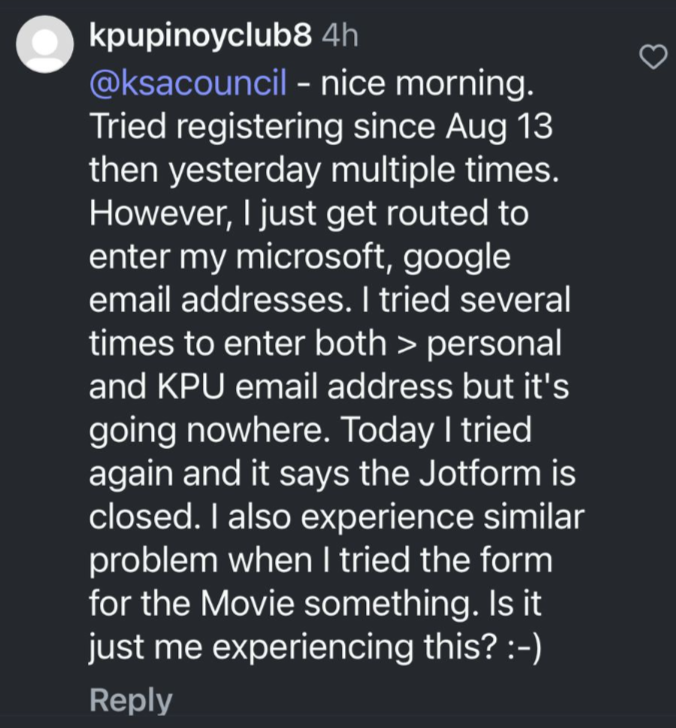

Then there is the events budget. Approved at $250,000, actual spending surpassed $750,000 — roughly three times the limit that had been set. Overspending by a few percentage points is normal in complex organizations. Overspending by hundreds of percent suggests that budget ceilings were no longer functioning as ceilings. If approved limits can be exceeded by half a million dollars, it is fair to ask whether the approval process retains meaning. Why hasn’t associate President Shawinderdeep (Shawinder) Singh nor VP Finance and Operations Manmeet Kaur provided any significant explanations other than seemingly Chat-GPT-esque vague written statements placing the blame at previous boards? Considering many were either part of those previous boards, it is simply arguably a laughable cop-out.

Recent reporting has included statements from KSA officials outlining proposed adjustments for 2026: reductions in legal allocations, tighter controls, restructured authority over certain expenses. Those proposals may prove constructive. But they are forward-looking. Students evaluating the situation should distinguish between what is promised and what has already occurred. The deficit is not hypothetical. The legal invoices are not projections.

What ultimately matters is not whether each individual expense can be defended in isolation. Large organizations can justify almost any single line item. The deeper question is whether the pattern reflects a student services organization or an institution increasingly occupied with managing its own turbulence.

A student union is not a corporation. It has no shareholders demanding quarterly returns. Its legitimacy rests on trust — the assumption that compulsory fees are spent transparently and prudently in the collective interest of students. When budgets tilt heavily toward legal costs, administrative growth, and spending overruns while service delivery appears uneven, that trust erodes quietly but steadily.

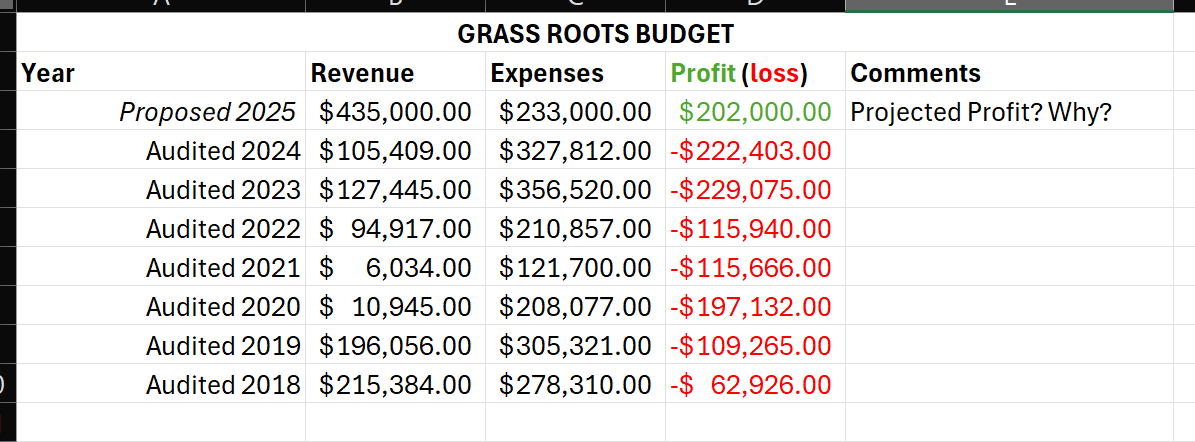

This budget seems to be a fantastical farce. Case in point, the Grassroots Cafe. It has never been a historical moneymaker, yet the budget continues to overestimate its revenue and underestimate its cost. The cafe was always meant to provide low-cost, subsidized, meal options to the student body. It was never meant to be operated as a profitable business. In 2023, its gross profits were $127,445 and expenses were $356,520, creating a loss of $229,075. In 2024, its profit was even less at $105,409 with expenses at $222,403 generating a loss of $222,403.

Yet in the latest proposed budget, they projected a revenue of $435,000 and expenses of $233,000. What would justify such a dramatic change in revenue? Considering that revenue has not exceeded $220,000 in the last 7 years…

Students must hold KSA representatives offering this pattern of inconsistencies to task. This is simply unacceptable accounting.

Ultimately, the issue is not simply that too much money was spent. The issue is that too much of it appears to have been spent managing problems rather than creating value. Until spending controls regain credibility and governance regains clarity, students are left with a budget that reads less like a plan for representation and more like a record of institutional self-preservation.

And numbers, unlike statements, rarely exaggerate.

Your words do carry weight. When used with intent, they can shift policies, spark dialogue, and protect what matters. 📩 Email KSA and KPU today.

SIGN THE PETITION: Demand forensic audit and transparency for Kwantlen Student Association.

As an active student, you have a right to attend council meetings to ask difficult questions on the record. If you want to attend, all you need to do is send a request to info@kusa.ca from your @student.kpu.ca email address.

Source:

Source: